OUR LAND, OUR ALTAR / A NOSSA TERRA, O NOSSO ALTAR

by André Guiomar

doc | dcp | 78’ | 2020

Synopsis

“Our Land, Our Altar” witnesses the latest daily routines in the Aleixo social housing, marked by the tension of a forced destiny. Between the fall of the first and the last tower, the demolition process has dragged on for years, leaving the lives of the residents in suspense. Obliged to accept the end of their community, they watch helplessly the slow disfigurement of their past.

Festivals and Awards

Ziff Youth Award, ZINEBI (ES)

Companhia das Culturas / Fund. Pereira Monteiro Award, Porto/Post/Doc (PT)

Honorable Mention, Film Festival Kitzbuehel (DE)

Best Feature, Kiev Film Festival (UA)

Best Documentary, Linea d'Ombra Festival (IT)

Best Film Outros Olhares, Caminhos do Cinema Português (PT)

Youth Award for Best Portuguese Feature, Festival CineEco (PT)

Portuguese Documentary Feature Honorable Mention, Festival CineEco (PT)

Best Documentary Film L’Europe autor de l’Europe (FR)

Sheffield International Documentary Film Festival (UK)

Doclisboa (PT)

Liberation Docfest Bangladesh (BD)

Älvsbyn Film Festival (SE)

Mostra Ecofalante de Cinema (BR)

Kaleidoskop – Film und Freiluft (DE)

Chichester International Film Festival (UK)

Beldocs IDFF (CS)

Matera Film Festival (IT)

CinemAmbiente (IT)

FIBDA - Festival Internacional de Cine Documental de Buenos Aires (AR)

DAFilms - Sheffield DocFest: Shifting Frames (online)

Tulum World Environment Film Festival (MX)

“Our Land, Our Altar is never explicitly political. It allows the viewer to draw their own conclusions but there is no doubting the forces of gentrification and the casual disregard for lives that don’t seem to matter. Guiomar speaks in a quiet, observant tone but his film is heard loud and clear.”

—Allan Hunter, ScreenDaily

“Keeping well out of frame, watching as a third party, the director is keen to witness the everyday. It's a place of washing lines, Hitchcockian stairwells, and domesticity. It might not be bliss, exactly, but it's home.”

—Kaleem Aftab, Cineuropa

“If there is one word to describe Guiomar's camera relationship with those Portuguese, it is tenderness. They deserved it. They just didn't deserve what happened to them afterwards.”

—João Antunes, JN

“A Nossa Terra, o Nosso Altar lives from fragments of a life that is fading away. It is remarkable the degree of "interiority" that the director has achieved"”

—Luís Miguel Oliveira, Público

50|50

by Mafalda Rebelo

Documentary | 4k | 73’

50|50 looks at the frustrations and triumphs that couples still encounter as they try to find a balance between raising children and working. Each story unveils the obstacles and prejudices that men and (mostly) women still have to overcome.

This documentary sheds light on the roads to conciliation, giving voice to ambitious, career-oriented women, but also to couples who are struggling to have children or to share their unpaid domestic duties fairly.

50 | 50 evaluates the advancements accomplished while also questioning whether the ongoing progress is sufficient in light of the times we live in.

AT SIXTEEN / AOS DEZASSEIS

by Carlos Lobo

fiction | HD | 14’20 | 2022

Synopsis

A school, a skatepark and a concert. Sara just turned 16.

Festivals and Awards

Best Director, Curtas Vila do Conde IFF (PT)

Berlinale, Generation Competition (DE)

Curtas Vila do Conde IFF (PT)

Vienna Short Festival (AU)

Sicilia Queer International LGBT & New Visions Filmfest (IT)

Mediterranean Film Festival Split (HR)

Guanajuato International Film Festival Expresión en Corto (MX)

Brest European Short Film Festival (FR)

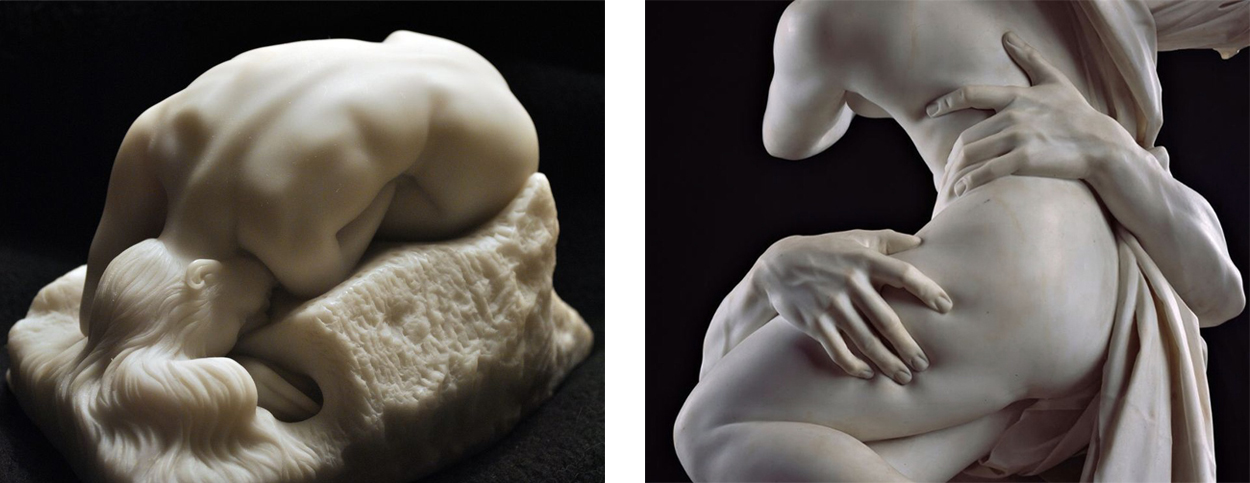

SATURN / SATURNO

by André Guiomar & Luís Costa

fiction | 16mm | 13’ | 2022

Synopsis

“Saturn” tells the story of Caveirinha, a humble fisherman who lives in a difficult social housing. Immediately after the death of his son at the sea, he faces the difficulty of burying him with dignity.

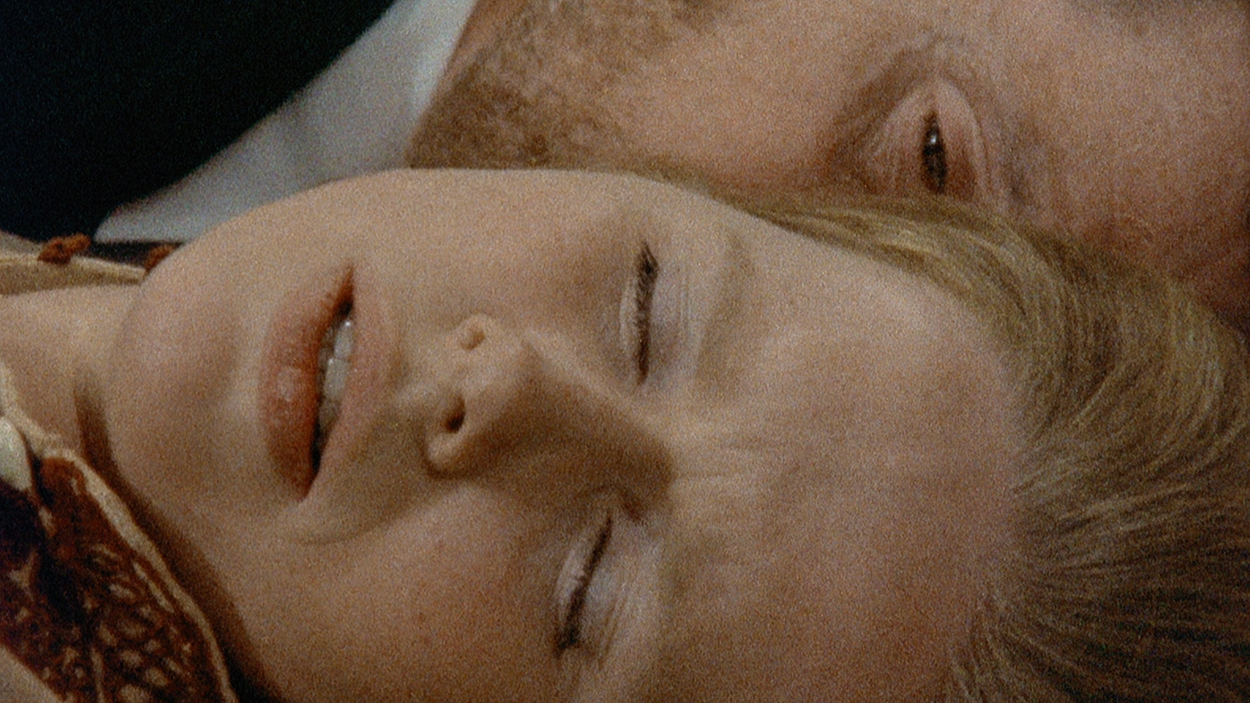

RIO GRANDE

fiction series | uhd | 52’ x 7 | in development

Genre

Historical drama

Rio Grande is the tale of a great number of Portuguese who, from north to south, left the countryside, sailing beyond the unknown, venturing into the excitement of the cities. It is a story of difficult choices and conflict between longing for the origins and the hunger to live better.

This epic journey also mirrors the times we currently live in, in which countless dangers and obstacles affect people fleeing their homes in search of safety, jeopardizing past civilizational advancements as well as the freedom to pursue happiness.

Rio Grande tells the story of the Alentejo migrant population who struggles to survive in a new city while harboring a strong desire to remain close to their ancestral home.

Synopsis

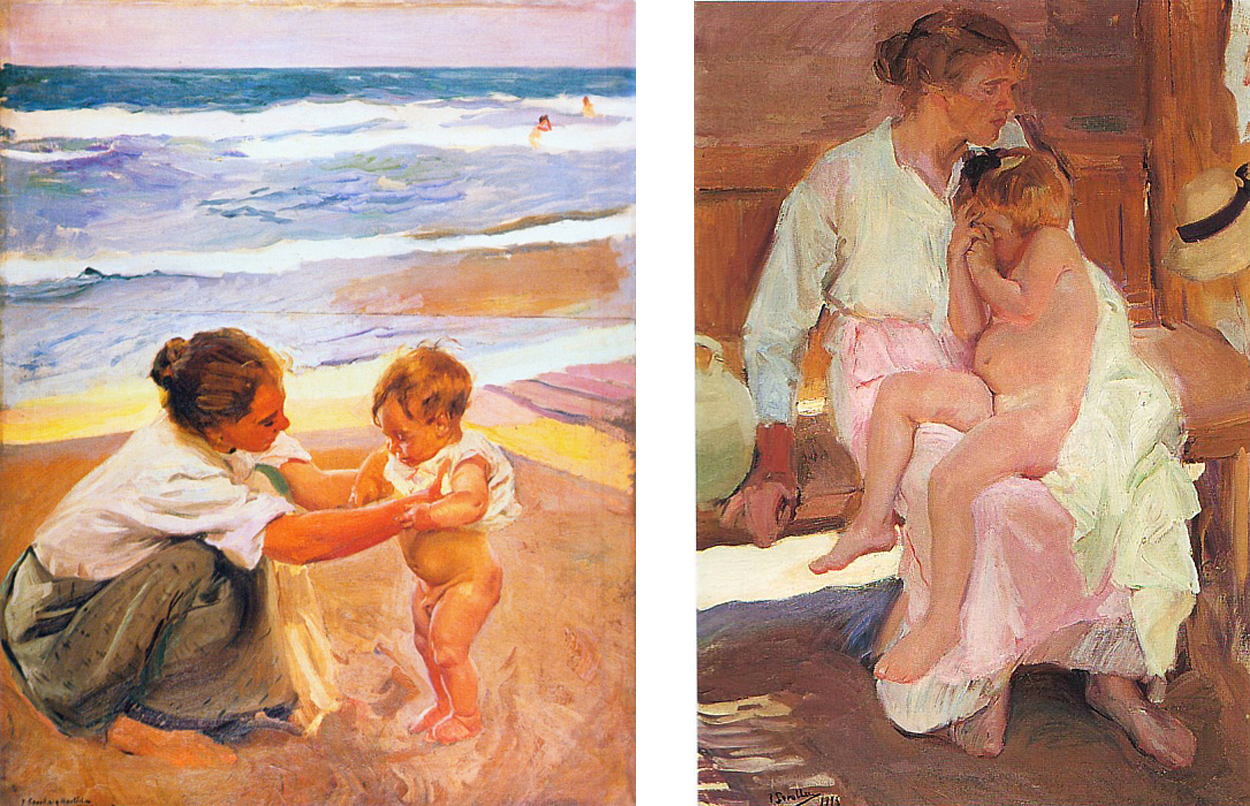

1996. The Rio Grande song "Postal dos Correios," which has become an anthem for many Portuguese generations, is playing on the radio. It tells the story of João Daniel and Laurinda Rosa, a couple born and raised in the hills of Alentejo, in the countryside of Portugal where there's hardly any work and the heat is extreme. They pack their whole lives into a bag and get on a bus to the suburbs of the capital. Like so many thousands from the rural areas, they're looking for a better life.

On the banks of the Tagus, in the vibrant Portuguese capital, where everything goes faster, Laurinda and João Daniel become accustomed to balancing their lives between the new freedom and the nostalgia of a distant home. João Daniel works at Lisnave, one of the world’s leading ship repair companies. While Laurinda, a dressmaker, aspires to become a more independent woman.

Like the river that never stops, the family's aspirations are challenged every day. The birth of their son Matias, the ongoing labour struggles and a democratic revolution are all part of the chaos that fills their lives. When the grown-up Matias is forced to leave his own country, João Daniel and Laurinda must rediscover who they are, after being gone for so many years from their eternal home in remote Alentejo. How will they close their migration cycle? Going back to their origins, or embracing the future in the city? Is their love strong enough to resist so many changes and obstacles? Can their love withstand all the changes and difficulties of a lifetime?

This is the tale of a great number of Portuguese who, from north to south, left the countryside, sailing beyond the unknown, venturing into the adventure of the cities. It is a story of choices, struggles, and navigating between nostalgia and the hunger to live better.

Background

Rio Grande tells a story against the backdrop of some of the most significant social changes that occurred in Portugal in the second half of the 20th century. In contrast with the north of the country, where it was more common for agricultural workers to own small plots of land that they could use to support themselves, there were pronounced social inequalities in the agricultural environment of Alentejo, where latifundia farming determined that most people were seasonal workers, without their own means of subsistence.

Around 50% of the agricultural land was owned by just 2% of the farmers in Baixo Alentejo. Therefore, the benefits of farming primarily benefited landowners and large and medium-sized farmers, leaving the laborers in precarious situations that frequently required them to turn to the work of all family members, specifically the children, to ensure subsistence and supplement the waged work of the men. The country's authoritarian political climate made the workers' situation even more challenging because any wage demands were met with violent retaliation from employers and authorities who supported the regime.

The 1960s brought about a change in the situation as a result of increased mechanization, which reduced the number of farmers in Alentejo, creating fewer job opportunities and making it harder for lower-income families to survive. Populations resorted to migration as one of their only options for survival. The number of migrants increased, particularly from Alentejo and Algarve, with major metropolitan areas in European nations like Germany and France as final destinations.

However, migration also occurred internally, and the rural exodus intensified towards the Portuguese larger cities, a phenomenon which today explains the desertification of the countryside. The changes, nevertheless, have not eliminated the struggles, as life in the city for migrants from poorer regions was marked by low wages and very demanding work. As a result, many families from Alentejo and Algarve were forced to relocate to the suburbs of the capital, where it was easier to find work and pay the rent. A prominent example of this influx of workers from all over the nation is the city of Almada, where many of them worked in the region's expanding naval sector in the 1960s. The installation of Lisnave in Margueira's yard in 1967 provided many jobs for the migrants. Lisnave alone had over 10,000 employees, one of the largest worker concentrations in the nation.

Despite the company's success, the challenging working conditions aggravated the relationship between employees and management, which worsened irrevocably in the 1980s. As a result of the decline in international orders, which is partly attributable to the oil crises of the 1970s, many workers were sent to "unemployment halls," where numerous men accustomed to above-national average wages, found themselves without a task to perform, receiving only the minimum wage.

Major strikes were organized by the workers in 1982 and 1983, but they were unable to stop the mass layoffs of employees or the radical redesign of Lisnave, which culminated in the decision to move the facilities to Setúbal in 1993 after a merger with Setenave, another ship repair company.

Rio Grande takes place in this setting of ongoing social unrest, where migrant populations from Alentejo struggled to survive in a new city while harboring a strong desire to stay connected to their roots. Almada is a paramount example of this phenomenon of trying to re-establish ties to one's native land, as evidenced by the proliferation of Alentejo singing groups and recreational, cultural, and sports associations in this Lisbon suburb. These institutions occupied the scarce free time that workers have between long workdays. They enabled the new generations born in the city to retain their roots while also aiding in the preservation of the lifestyles and traditions of Alentejo.

The epic journey portrayed in Rio Grande is both a nostalgic look back at a bygone era and a reflection of the times we currently live in, which are characterized by global unpredictability and daily threats to past civilisational advances and the pursuit of freedom. Rio Grande will look for answers that those who migrate in search of a better life have not yet been able to find.

Writers’ statement

Rio Grande is a journey inspired by the album with the same name, written by the poet João Monge, which paid homage to his family who emigrated from Alentejo in search of a better life. But Rio Grande is also the story lived by our parents, their brothers and sisters who were forced to leave their land in search of work because they lacked the opportunities offered by urban areas. The same story is still being experienced today by our friends that leave their home countries in search of a more promising future somewhere else in the world. The same is happening throughout the world as war and natural disasters keep displacing millions of people.

Rio Grande will closely observe the contradictions of the migratory phenomenon. Where do we find happiness: sailing off to surpass new horizons or satiating the eternal longing that draws us back to our roots? How can we alleviate this permanent dissatisfaction?

To discover the answers, we will follow the adventures and misadventures of João Daniel and Laurinda, a couple from Alentejo that moved to the Lisbon suburbs in search of a better life. A tale that has already been sung by the legendary Rio Grande vocal group, which featured five of the country's most well-known performers, but also by any Portuguese who lived through the 1990s. This is a migration story that has not yet been told. We'll follow João Daniel, the boy with the slingshot in his back pocket and Laurinda, the girl who makes made-to-measure dresses, as they navigate their life's challenges.

While Laurinda looked forward to the potential opportunities that moving to the city might bring, João Daniel left Alentejo with his thoughts on the day of the return. He, who longed for the warm land where he learned to run barefoot, was dumped in the belly of a ship, without ever having seen the sea. A tiny ant in Lisnave, a city within the city, the epicenter of a revolution that raged in ceaseless shifts, where boats bigger than the world are repaired, and the canteens fill up with hundreds of workers demanding better working conditions. But Laurinda holds her newborn son Matias in her tiny one-bedroom apartment as she looks across the river at a new world that appeals to her, full of opportunities, but whose doors are unlikely to open to an uneducated woman with limited resources. She conforms to the expectations that society has placed on her, and struggles to fall asleep, spinning around in bed, worrying that her ambitions can only be achieved through her husband.

Laurinda and João Daniel struggle to stay together amidst so many currents and countercurrents, many times in disagreement. During the tumultuous Strike of 82 at Lisnave, João Daniel is forced to choose between loyalty to his fellow workers, many from his own Alentejo, and a job that secures a future for his wife and son. Laurinda, however, believes that there is something more for the family: education, a better house, and access to the culture of the capital, so she juggles between multiple jobs while sewing everyday until dawn. But if hard work prevents them from living happily, how can they make it through their journey?

With this couple that struggled in suburban Almada, just as our parents did in other suburban areas of the country and millions of migrants keep doing everyday, we will revisit a time of significant social upheaval: the Carnation Revolution, the Lisnave crises of the 1980s with its mass layoffs. We will pay close attention to this family's tireless efforts to provide their son with the opportunities they never had. A son who - like us - grew up in the voluptuousness of the city, incapable of ignoring the genetics of his origins, leading to new contradictions and conflicts that we plan to explore in Rio Grande.

In our research, we interviewed the author João Monge, former Lisnave employees, and residents of Alentejo and Almada. And to get a feel for Alentejo and the epoch, we visited Serpa, Ficalho, Lisnave and the Almada Naval Museum.

João Monge began to tell the Rio Grande story for the first time when he imagined his father's journey from Alentejo. When we first learnt about Rio Grande, we were only teenagers and had no clue that it was also our story, the story of our friends and relatives, the story of people who fight to find a better life away from their beloved home.

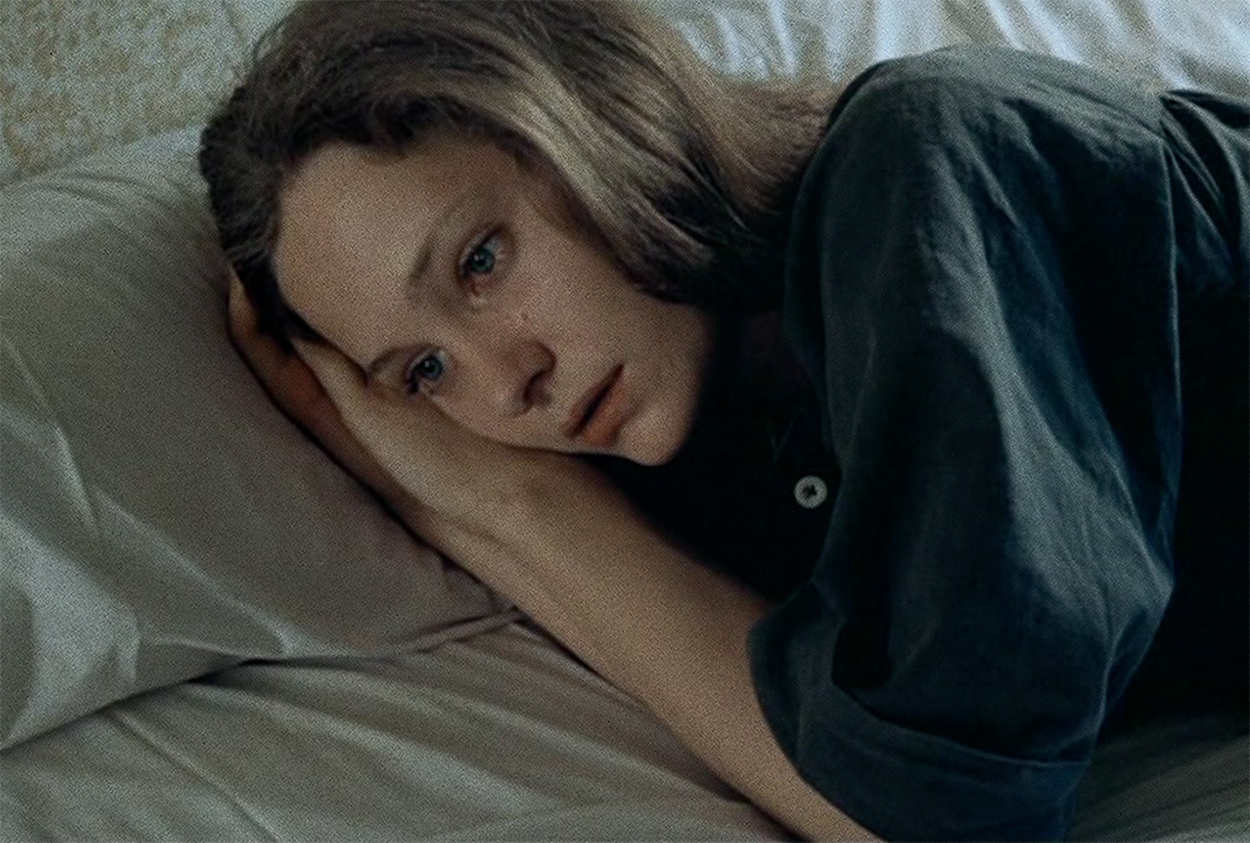

WHAT REMAINS | A NORMALIDADE

by André Guiomar

fiction film | in development

Logline

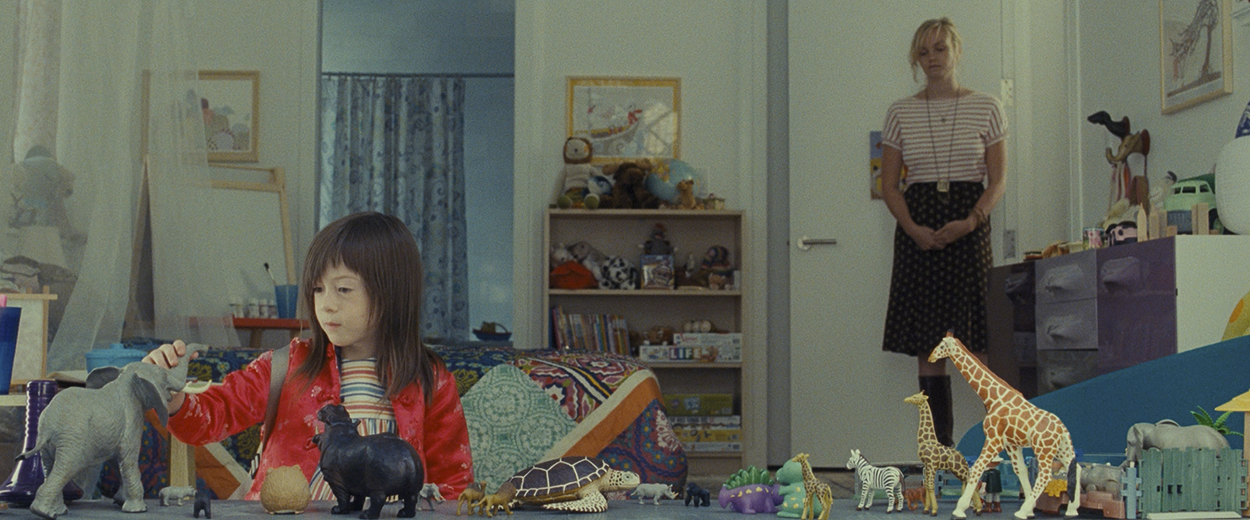

Marta and Rogério were expecting a child like all the others. A child ready to grow, a common desire for normality. Henrique's autism diagnosis comes to shake the relationship, confronting them with their own differences.

Project presentation

When a child is born, it is always expected to be perfect, without limitations, ready to grow. Marta and Rogério had this child until the age of two, but small signs were emerging that the future would not be so linear. As a human being walled in by silence, Henrique is diagnosed with autism. The illness isolates him from the world, and from his parents' affection. The evidence takes shape and an arduous journey from treatment to treatment begins, between faith and resignation. The couple's expectations, shattered by the disease, end up eroding their relationship. The unpredictability makes the restlessness of each one's existence a constant. In this tumultuous atmosphere, the most surprising thoughts appear.

Based on the novel “Autism” by Valério Romão, the author evokes the impotence of those who are close to sickness and focuses attention on a disease that is little assimilated in contemporary society, with inadequate responses and a varied offer of unproven alternative therapies. The disarming of those who can do nothing in the face of illness where the couple is faced with loneliness, failure and impotence, but also the selfless struggle, obstinacy, the impulse where there was no longer any strength. At the heart of despair, the narrative invokes the differences between man and woman and between father and mother: the masculine point of view, seeking order through logic, in a blind but limited delivery of love, and the feminine that represents complexity, “the unpredictability of the infinite wealth of nature” (Franco Berardi), the love that, through osmosis or lack of solution, carries the child even more in an attempt to cure by compensating of parts. Autism is not the only obstacle in this family.

“Like everyone else, we have plans, and they are the anchors that we throw to the future, so that we can move our arms towards it.” (Valério Romao)

DIA-A-DIA

by Luis Pedro Cardoso

short fiction film | in development

GDA grant confirmed

Logline e Sinopse

Um dia na vida de um casal que nem tempo tem para discutir.

Joana e Miguel são um casal com dois filhos. Um dia, depois de mais uma manhã a correr em contra-relógio, um comentário no carro na ida para o emprego, cria um ambiente de tensão e dúvida.

Até ao final do dia, procuram arranjar oportunidade para clarificar em que ponto está a relação. Mas, com todas as solicitações, o dia passa a correr. Nem sempre como se deseja.

Este filme pretende oferecer um olhar honesto e realista sobre a vida familiar, sem romantismos ou idealizações. Pretende explorar como a rotina e as obrigações podem colocar pressão em qualquer relação, e como muitas vezes as emoções e questões importantes são deixadas de lado por falta de tempo ou oportunidade.

Nota de intenções

Há algum tempo atrás, após uma noite mal dormida, envolvi-me numa discussão com a pessoa com quem partilho a vida e todos os dias. A vida interpôs-se, fomos interrompidos diversas vezes e, por causa disso, não conseguimos esclarecer o conflito nesse mesmo dia. Esta experiência despertou em mim uma reflexão mais profunda sobre o cuidado das relações na vida contemporânea. E encontrei uma história que me interessa contar: um casal que não tem tempo sequer para resolver os seus problemas. A simplicidade, realismo e pertinência desta premissa, motivaram-me.

Numa vida em que tento conciliar uma carreira cinematográfica, a gestão de uma produtora e o cuidado de três filhos, tenho experimentado, ao longo do tempo, como a conjugação da vida pessoal e profissional pode ser intensa e desafiante. A harmonia é um estado difícil de alcançar e preservar.

Recentemente, o confronto com vários projectos que, pelas suas urgências e dimensões, foram condicionando a minha capacidade de presença e resposta para manter esta harmonia, suscitou em mim uma vontade irreprimível de expressão.

Dia-a-dia é uma curta-metragem que parte da ideia de um casal que não tem sequer tempo para resolver os seus problemas. Pretende oferecer um olhar honesto e realista sobre esta vida partilhada, sem romantismos ou idealizações. Pretende explorar como a rotina e as obrigações podem colocar pressão em qualquer relação, e como muitas vezes as emoções e questões importantes são deixadas de lado por falta de tempo ou oportunidade.

Interessa-me refletir sobre como a rotina do dia-a-dia tantas vezes transforma a relação de casal numa gestão de tarefas e obrigações, deixando pouco tempo para a relação (muito menos para si mesmos). Mesmo problemas e conflitos importantes muitas vezes têm de ser adiados por falta de tempo ou contexto adequado para os enfrentar. É uma reflexão sobre como qualquer relação, por mais saudável que seja, enfrenta desafios e dificuldades no dia-a-dia acelerado e exigente, perdendo-se algo pelo caminho.

É também um olhar sobre a sociedade da “qualidade de vida” que promete que está ao nosso alcance ser e fazer o que quisermos mas se torna avassaladora e indigerível com tantas expectativas, tarefas, funções, identidades e papéis que nos sentimos compelidos a abarcar.

Este é um filme sobre um casal normal numa vida normal: com inúmeras tarefas a cumprir e vários papéis a desempenhar, sempre em corrida, sempre um bocadinho a falhar, sempre com pouco tempo para os outros e para a relação. Neste mundo acelerado estão em prontidão: ao alcance de um email, de uma chamada ou de uma solicitação dos chefes, em função das crianças nas inúmeras atividades extracurriculares e a corresponder a obrigações que enchem os dias mas não preenchem.

Centrados em Miguel (personagem principal) vemos o mundo em redor dele, e a forma como o afecta e conforma. Acompanhamos as suas vivências, os seus movimentos, as suas moções e a forma como procura lidar e estar à altura das circunstâncias. Vive num ritmo acelerado. Está exausto. Sente-se desligado, mas procura conectar-se, cumprir, estar à altura do seu papel e não falhar. Parece procurar uma felicidade que lhe escapa. Como vemos o seu ponto de vista, experienciamos, na primeira pessoa, o desconhecimento do que se passa com o outro e a perturbação e insegurança que daí advêm. É um homem que não se sente realizado nas tarefas que faz, nas relações que tem, na forma como a vida se impõe. Não tem sequer tempo para pôr as coisas em causa, para conversar, para debater e encontrar novos caminhos porque a voragem dos dias é demasiado intensa. Até estar instalada a crise - já em aparente ruptura - parece nunca haver tempo para parar, refletir e implementar ajustes. Há que sobreviver e tentar cumprir. E a realidade impõe-se, deteriora e deslaça as relações na voracidade dos dias.

Este filme capta um dia concreto na busca deste equilíbrio ténue (e sempre transitório!). Um casal submergido na correria dos dias procura vir à tona para se situar e respirar. Voltarão - voltamos todos! - a ser engolidos no frenesim da vida com uma quantidade de ar que lhes vai permitir prosseguir por algum tempo, até começarem de novo a sufocar e a sentir-se em perigo. Aí voltarão a batalhar para respirar de novo, arriscando poder ser já tarde demais.

Este filme é também isto: uma tentativa de respiro. Encorajado por amigos colegas, criativos e atores, sinto finalmente que chegou o momento de apresentar a minha visão.

Luis Pedro Cardoso

LAR DOCE LAR

by Mafalda Rebelo

documentary | in development

Sinopse

Um olhar sobre a habitação - o lar - desde o ponto de vista de famílias concretas, apreciando o impacto e as opções distintas no dia-a-dia: a compra ou aluguer de casa, as escolhas profissionais, o número de filhos, as deslocações diárias ou o êxodo urbano... o que é a qualidade de vida?

Contextualização

Os pássaros fazem ninho por pouco tempo, criam os filhos e vivem o resto do tempo “livres”, com a liberdade (e a responsabilidade também) de migrarem atrás das condições certas.

Desde que os humanos deixaram de ser nómadas recolectores, desenvolvemos enormes capacidades técnicas que nos permitem controlar e contrariar situações adversas e fixarmos-nos, podendo construir incrementalmente coisas duráveis: desenvolver casas, agricultura, técnicas e saberes elaborados. Esta realidade não é igual em todo o lado, sendo que em locais inóspitos e mais adversos à presença do homem, o homem desenvolveu estratégicas, técnicas e previdências mais elaboradas.

A fábula da “Cigarra e a Formiga” levanta estas questões em forma de moral. Mas porquê construir uma grande casa de tijolo, bem isolada e com acabamentos rigorosos em terras quentes e favoráveis à agricultura todo o ano? As pessoas podem abrigar-se num palheiro e poupar tempo, canseiras ou dinheiro para outros prazeres. Já se se for habitante de uma região nórdica, onde metade do ano o clima é rigoroso, as árvores estão despidas e a neve cobre toda a natureza, terá naturalmente de se ser previdente como a formiga para se poder sobreviver.

Independentemente do local e do contexto, a casa é um direito fundamental. Em Portugal, trata-se do 1º direito da nossa Constituição: “Todos têm direito, para si e para a sua família, a uma habitação de dimensão adequada, em condições de higiene e conforto e que preserve a intimidade pessoal e a privacidade familiar.”

“À primeira vista poderia parecer insólito que um tema, como o da habitação, constituísse uma questão de direitos humanos. Basta, porém, observar o direito internacional ou as legislações nacionais, e pensar em tudo o que um lugar seguro para viver pode representar para a dignidade, a saúde física e mental e a qualidade geral de vida do ser humano, para que se comecem a revelar algumas das implicações da habitação, no domínio dos direitos humanos. Dispor de uma habitação condigna é universalmente considerada uma das necessidades básicas do ser humano”.

Evoluímos já muito desde os tempos - não tão distantes - das casas humildes, sem casa de banho, sem espaço mínimo ou qualquer isolamento. Os anos do pós 25 de Abril representaram um tempo de crença no progresso e de acesso mais generalizado a condições de vida melhoradas, com eliminação de bairros de lata, generalização do saneamento público, construção colectiva e cooperativa e créditos bonificados.

Mas dos tempos das “ilhas” e da convivência - até forçada - entre os vizinhos, viemos desembocar numa época de indiferença, cada qual no seu casulo, tendencialmente sem hábitos de vizinhança, comunidade ou redes de apoio.

Isto é amplamente potenciado pela falta de pertença ao local onde se vive, muitas vezes por impossibilidade de compra nas zonas onde as redes estão estabelecidas.

“A noção de habitação condigna é definida na Estratégia Global como compreendendo: intimidade suficiente, espaço adequado, segurança adequada, iluminação e ventilação suficientes, infra-estruturas básicas adequadas e localização adequada relativamente ao local de trabalho e aos serviços essenciais – tudo isto a um custo razoável para os beneficiários.”

Neste aspecto da conjugação do “custo razoável” com “localização adequada” - já sem falar do “espaço adequado” - é que a realidade atual atraiçoa as famílias que ainda não compraram casa e pretendem fazê-lo ou precisam de mudar.

Se se é um nómada digital ou se se tem uma família a cargo, as percepções, opções e oportunidades são muito distintas. Os binómios liberdade-segurança, oportunidades-ameaças, ofertas culturais-possibilidade de acesso, são pesados de forma diversa.

Localização, áreas, acabamentos, acessos, trânsito e transportes têm de ser pesados face a custo, acesso a crédito, rendas, custos fixos, taxas de esforço. Muitas famílias estão fora do sistema presas na falta de opções reais, que tornam impossível a gestão do dia-a-dia.

Nesta época em que a habitação é um ativo financeiro e as cidades estão cheias de casas a valorizar, turistas e nómadas digitais, os êxodos urbanos tornam-se uma realidade (escolhida ou forçada) e as famílias convertem-se em “novos povoadores”.

Abordagem

No mesmo tipo de linguagem do documentário anterior “50|50”, este é um documentário centrado nas opções das famílias.

Como balanceam tudo?

O número de filhos, a compra ou aluguer de casa, as escolhas profissionais, as deslocações e a desejada qualidade de vida... que opções tomam? Que opções são obrigadas as tomar? O que ganham e o que perdem? Que impactos tem no tempo, disponibilidade e acesso às ofertas culturais, recreativas ou desportivas?

Que valores e estilo de vida privilegiam diferentes famílias?

Documentaremos famílias das grandes cidades com empregos desafiantes, bem remunerados mas exigentes de tempo e disponibilidade, e famílias que trocaram (algumas foram obrigadas a trocar) a cidade por cidades ou vilas mais pequenas - com menos ofertas (será?) mas com mais controlo do custo de vida.

Como se educam as crianças nos vários contextos?

Quais são os prós e os contras?

O que é a qualidade de vida?

A PRÓXIMA PEÇA

by Henrique Prudêncio

documentary | post-production roughtcut

Sinopse

Durante mais de um ano, a companhia ArQuente, esteve em laboratório com um leque de pessoas diversas da cultura de Faro, à procura do que haviam de retratar.

A maioria deles com vidas completamente díspares do teatro, experiencia essa arte de forma apaixonadamente diferente. As conversas sobre o que os une, o caos da tecnologia, o seu dia-a- dia, como transformar tudo isso numa peça e o que vale a pena comunicar ao público.

Nota de intenções

Gil, o encenador desta peça, diz em tom de brincadeira no fim deste filme que eu fiquei com este documentário surrealmente inacabado. E du- rante largos anos, também pensei que sim. O que no início era apenas um filme para retratar um processo de uma peça de Janeiro até Maio, acabou por se estender num laboratório terapêutico para os seus intervenientes durante um ano. Nenhum de nós estava pronto para isso, com várias di- ficuldades sentidas durante o processo de rodagem em ter uma equipa fixa sem remuneração e motivação. Muitas vezes dei por mim a perguntar porque estava eu a filmar aquele grupo à deriva.

Contudo, eu sabia que, eventualmente, existiria um conflicto. As tensões entre o grupo eram notórias. Uns queriam estar lá para ultrapassar limites próprios, outros queriam apresentar e dar o seu contributo a um público.

E quando o António, o nosso protagonista, sai do ensaio a meio, dei- me grato por ter tido a paciência depois de 9 meses para descobrir o que estava a filmar.

Este é um filme sobre processos artísticos. O que leva a um grupo para se juntar e querer apresentar uma peça? Vale a pena apresentar algo, quando não se tem nada para dizer? É mais importante o colectivo ou o individual? Tudo isto são questões que julgo pertinentes e que me levar- am a montar o filme, seis anos depois.

O teatro é muito importante para mim. Enquanto cresci, era uma con- stante na minha vida, seja em contexto escolar, amador, ou profissional. E sempre tive a sensação egoísta de me saber bem, de ter saudades dele, do sofrimento e da euforia que causa. Apresentar para um público era um processo secundário e de cumprimento de dever. Como actor, não era isso que me interessava. Queria explorar e quebrar os meus limites.

Por isso, não deixo de empatizar com este grupo da ArQuente, que sem ta- bus e sem pudor, fala sobre esse egoísmo e o explora. Que assume aquilo que tão poucas pessoas o fazem.

Mas o que acho de uma dicotomia interessante é que eu sentia essa empatia enquanto os criticava mentalmente, por estarem a usar um es- paço maravilhoso, por terem um grupo fenomenal e não apresentarem nada. Aquilo afectava-me, psicologicamente e fisicamente. Era revoltante e gritante.

Durante este processo, nestes 6 anos, estive extremamente dividido sobre o que pensar do grupo, do seu encenador e deste filme. Tinha medo de o concluir porque tinha receio de não os entender e de só criticar.

Transmitir esta dicotomia então é o que sinto que posso dar para fazer jus às pessoas. Fazer entender os indivíduos, quem são eles, ao mesmo tempo que os quero retratar de umaforma crua. Para fazer debater, sem dúvida, mas também para fazer entender que há um outro lado por detrás dos processos artísticos. Que talvez julgamos demasiado cedo antes de ter empatia pelo outro. Que todos nós temos vidas pessoais, com processos muito duros e que acaba irremediavelmente por interferir nas criações artísticas.